SOLID OO Design: The Complete Guide to Writing Clean Code

TL;DR

- SOLID is a collection of five object-oriented design principles—Single Responsibility, Open-Closed, Liskov Substitution, Interface Segregation, and Dependency Inversion—intended to make software easier to maintain, scale, and extend.

- The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) encourages every class to have one clear purpose, reducing code complexity and improving testability by ensuring classes only change for one reason.

- The Open-Closed Principle (OCP) ensures that code is open for extension but closed for modification, helping systems grow through new features or modules without altering existing, tested logic.

- The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) mandates that subclasses must be usable through their parent class interface without unexpected behavior, ensuring correct and predictable inheritance hierarchies.

- The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) favors many small, focused interfaces over large, general-purpose ones, so implementing classes depend only on what they actually use.

- The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) directs both high-level and low-level modules to rely on abstractions—leading to flexible, modular systems adaptable to change and ideal for scalable cloud or microservice architectures.

If you’ve been in the software development world for any length of time, you’ve probably heard the term SOLID. It’s one of those concepts that gets thrown around in code reviews, architectural discussions, and technical interviews. But what does it actually mean? And more importantly, why should you care?

After more than a decade of building software, I can tell you that understanding and applying SOLID principles is one of the most significant steps you can take to level up your coding skills. It’s the difference between writing code that simply works and crafting software that is a joy to maintain, extend, and test.

This guide is designed to be your go-to resource for SOLID. We’ll break down each of the five principles with simple explanations and practical, real-world examples. By the end, you’ll not only understand the theory but also know how to apply it to build robust, scalable, and maintainable software architecture.

What Is SOLID in Object-Oriented Design?

SOLID is an acronym that represents five core principles of object-oriented design. These principles, when applied together, help developers create software systems that are more understandable, flexible, and maintainable.

Origin and Definition of SOLID

The SOLID principles were introduced by Robert C. Martin (also known as “Uncle Bob”) in the early 2000s. While he developed the principles, the acronym itself was later coined by Michael Feathers. These principles are a subset of many software engineering principles promoted by Martin.

SOLID stands for:

- S – Single Responsibility Principle

- O – Open-Closed Principle

- L – Liskov Substitution Principle

- I – Interface Segregation Principle

- D – Dependency Inversion Principle

Think of these not as strict rules, but as guidelines that help you avoid common “code smells” and design flaws that lead to rigid and fragile code.

Why SOLID Is Essential for Modern Software Development

In today’s fast-paced development environment, requirements change, new features are added, and bugs need fixing. Without a solid foundation, a software system can quickly become a “big ball of mud”—a tangled mess of code that is difficult to change without breaking something else.

SOLID principles provide a framework for creating systems with high cohesion and loose coupling. High cohesion means that the elements within a module belong together, while loose coupling means that modules are independent of one another. This structure is the hallmark of a well-designed system.

Benefits of Using SOLID in Real Projects

From my experience, teams that consistently apply SOLID principles see tangible benefits:

- Reduced Complexity: Code becomes easier to understand because each part has a clear and focused purpose.

- Increased Maintainability: Changes can be made with more confidence, as modifications in one area are less likely to have unintended side effects elsewhere.

- Improved Testability: Loosely coupled components are easier to isolate and test, leading to more reliable unit tests.

- Enhanced Scalability: A well-structured system is easier to scale and extend with new functionality.

What Is the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)?

The first and arguably most fundamental principle is the Single Responsibility Principle. It’s a simple idea with profound implications for how you structure your classes.

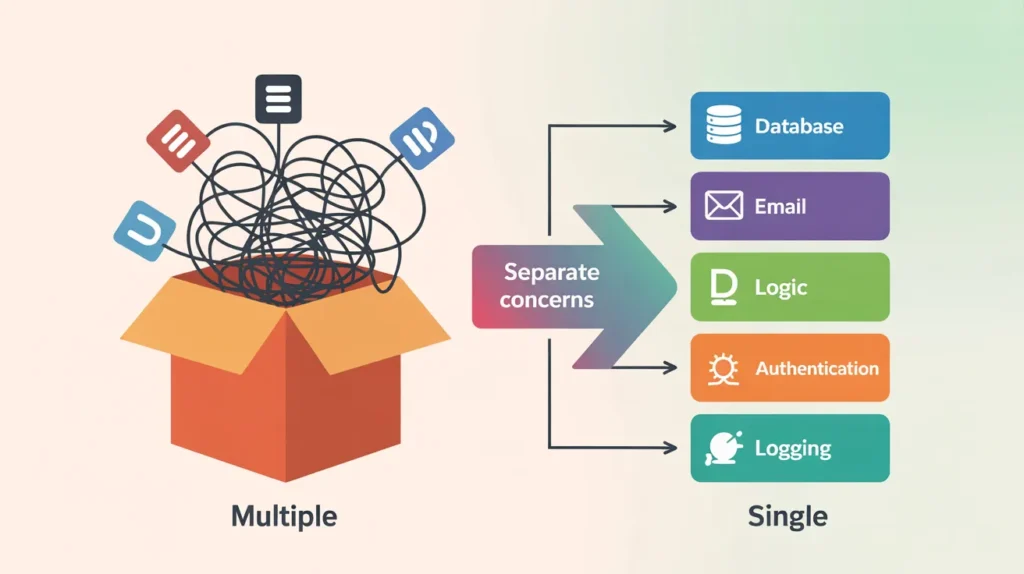

Meaning of SRP with Simple Explanation

The Single Responsibility Principle states that a class should have only one reason to change. This doesn’t mean a class should only do one thing, but that all the things it does should be related to a single, primary responsibility.

A common misconception is that SRP is about having only one method in a class. That’s not it. Instead, think about the actors or roles that might request a change. If a class serves more than one actor, it has more than one responsibility.

Real-World Example of SRP in OOP

Imagine a User class that handles both user profile management and database operations.

// Anti-SRP Example

class User {

private String name;

private String email;

public void saveToDatabase() {

// Code to save user to DB

}

public void sendWelcomeEmail() {

// Code to send an email

}

}

This User class has two reasons to change:

- If the database schema changes (a persistence concern).

- If the content of the welcome email changes (a notification concern).

A better approach is to separate these responsibilities:

// SRP-Compliant Example

class User {

private String name;

private String email;

// Getters and setters

}

class UserRepository {

public void save(User user) {

// Code to save user to DB

}

}

class EmailService {

public void sendWelcomeEmail(User user) {

// Code to send an email

}

}

Now, each class has a single responsibility. UserRepository is only concerned with persistence, and EmailService is only concerned with notifications.

How SRP Reduces Complexity and Makes Code Testable

By following SRP, our code becomes much cleaner. When you need to debug a database issue, you know to look in UserRepository. If there’s a problem with emails, you go straight to EmailService. This separation makes each class smaller, more focused, and significantly easier to test in isolation.

What Is the Open-Closed Principle (OCP)?

The Open-Closed Principle guides us on how to build software that can be extended without being modified. It’s a cornerstone of creating plug-in architectures and maintainable systems.

Explanation of OCP and Why It Matters

The OCP states that software entities (classes, modules, functions) should be open for extension but closed for modification.

- Open for extension: You should be able to add new functionality without changing existing code.

- Closed for modification: Once a component is developed and tested, its source code should not be changed to add new features.

This principle is crucial for building stable systems. Every time you modify existing, working code, you risk introducing new bugs. By extending instead of modifying, you minimize that risk.

Example: Extending Behavior Without Modifying Code

Consider a ShapeCalculator class that calculates the total area of different shapes. A naive approach might use a series of if/else statements.

// Anti-OCP Example

class ShapeCalculator {

public double calculateTotalArea(Object[] shapes) {

double totalArea = 0;

for (Object shape : shapes) {

if (shape instanceof Circle) {

totalArea += Math.PI * ((Circle)shape).radius * ((Circle)shape).radius;

} else if (shape instanceof Rectangle) {

totalArea += ((Rectangle)shape).width * ((Rectangle)shape).height;

}

// What if we add a Triangle? We have to modify this method!

}

return totalArea;

}

}

To add a new shape, like a Triangle, you have to modify the calculateTotalArea method. This violates OCP.

A better design uses an interface and polymorphism:

// OCP-Compliant Example

interface Shape {

double calculateArea();

}

class Circle implements Shape {

public double radius;

public double calculateArea() {

return Math.PI * radius * radius;

}

}

class Rectangle implements Shape {

public double width;

public double height;

public double calculateArea() {

return width * height;

}

}

class ShapeCalculator {

public double calculateTotalArea(Shape[] shapes) {

double totalArea = 0;

for (Shape shape : shapes) {

totalArea += shape.calculateArea();

}

return totalArea;

}

}

Now, to add a Triangle class, you simply create a new class that implements the Shape interface. The ShapeCalculator class does not need to be modified at all. It is closed for modification but open for extension with new shapes.

How OCP Supports Plug-in or Modular Architecture

This pattern is the foundation of modular systems. By relying on abstractions (like the Shape interface), you can create core components that work with any new module that adheres to that abstraction. This is how plug-ins for applications like WordPress or VS Code work.

What Is the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)?

The Liskov Substitution Principle is all about ensuring that your abstractions are correct and that subtypes behave as expected.

Definition of LSP with Simple Analogy

Named after Barbara Liskov, the LSP states that objects of a superclass should be replaceable with objects of its subclasses without affecting the correctness of the program.

A classic analogy is the “Rectangle-Square” problem. Mathematically, a square is a rectangle. But in object-oriented programming, if a Square class inherits from a Rectangle class, you can run into trouble. A Rectangle has independent width and height properties. If you set the width, the height shouldn’t change. However, for a Square, setting the width must also set the height. This difference in behavior violates LSP, as you can’t substitute a Square for a Rectangle without causing unexpected behavior.

Common LSP Violations in OOP

LSP violations often occur when a subclass:

- Throws new exceptions not thrown by the superclass method.

- Returns a different type than the superclass method.

- Does nothing in an overridden method, or throws an

UnsupportedOperationException.

For example, imagine a Bird class with a fly() method. If you create a Penguin subclass that inherits from Bird, what do you do with the fly() method? Penguins can’t fly. If you make it do nothing or throw an exception, you violate LSP because you can no longer treat a Penguin object just like any other Bird.

How to Ensure Classes Follow LSP

To follow LSP, ensure that your subclasses honor the “contract” of the superclass. This means:

- Method signatures must match.

- Preconditions cannot be strengthened in the subclass.

- Postconditions cannot be weakened in the subclass.

- Invariants of the superclass must be preserved.

In the bird example, a better design would be to have a Bird class and then separate FlyingBird and NonFlyingBird interfaces or abstract classes.

What Is the Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)?

The Interface Segregation Principle is about keeping your interfaces focused and small. It’s the SRP applied to interfaces.

Meaning of ISP

The ISP states that no client should be forced to depend on methods it does not use. This means you should favor many small, client-specific interfaces over one large, general-purpose interface.

Fat Interfaces vs Segregated Interfaces

A “fat interface” is an interface with too many methods, forcing implementing classes to implement methods they don’t need. This leads to bloated classes and unnecessary dependencies.

Segregated interfaces are small and focused on a specific set of behaviors.

Real-World ISP Example for Cleaner Code

Consider an interface for a Worker.

// Anti-ISP Example ("Fat Interface")

interface IWorker {

void work();

void eat();

}

class HumanWorker implements IWorker {

public void work() { /* ... */ }

public void eat() { /* ... */ }

}

class RobotWorker implements IWorker {

public void work() { /* ... */ }

public void eat() {

// Robots don't eat. This method is useless.

throw new UnsupportedOperationException("Robots don't eat!");

}

}

The RobotWorker is forced to implement the eat() method, which it doesn’t need. This is a violation of ISP.

A better approach is to segregate the interfaces:

// ISP-Compliant Example

interface IWorkable {

void work();

}

interface IEatable {

void eat();

}

class HumanWorker implements IWorkable, IEatable {

public void work() { /* ... */ }

public void eat() { /* ... */ }

}

class RobotWorker implements IWorkable {

public void work() { /* ... */ }

}

Now, RobotWorker only implements the functionality it needs, resulting in cleaner, more logical code.

What Is the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)?

The Dependency Inversion Principle is about decoupling modules. It’s a crucial concept for creating flexible and resilient software architecture.

High-Level Modules vs Low-Level Modules

In any system, you have high-level modules (which contain business logic) and low-level modules (which handle details like database access or network calls). A common mistake is to have high-level modules depend directly on low-level modules.

The DIP states two things:

- High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions (e.g., interfaces).

- Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions.

This “inverts” the typical flow of dependency. Instead of Business Logic -> Database, the flow becomes Business Logic -> Abstraction <- Database.

Why Abstractions Improve Flexibility

When high-level modules depend on abstractions, you can easily swap out the low-level implementation without changing the high-level code. For example, you could switch from a SQL database to a NoSQL database by simply creating a new class that implements the data access interface.

Using Dependency Injection to Apply DIP

Dependency Injection (DI) is a common technique used to implement DIP. Instead of a high-level class creating its own dependencies (the low-level modules), the dependencies are “injected” from an external source (like a DI container or framework).

// Anti-DIP Example

class NotificationService {

private EmailSender emailSender;

public NotificationService() {

this.emailSender = new EmailSender(); // Direct dependency on a concrete class

}

public void sendNotification(String message) {

emailSender.send(message);

}

}

// DIP-Compliant Example

interface IMessageSender {

void send(String message);

}

class EmailSender implements IMessageSender {

public void send(String message) { /* ... */ }

}

class NotificationService {

private IMessageSender messageSender;

// Dependency is injected via the constructor

public NotificationService(IMessageSender messageSender) {

this.messageSender = messageSender;

}

public void sendNotification(String message) {

messageSender.send(message);

}

}

In the second example, NotificationService depends on the IMessageSender abstraction, not the concrete EmailSender class. This makes the system much more flexible.

How to Apply SOLID Principles in Real Development Projects?

Theory is great, but the real test is applying these principles in your day-to-day work.

Applying SOLID to APIs, Microservices, and Back-end Systems

- Single Responsibility Principle: Design your API endpoints and microservices to have a single, well-defined purpose. An

OrderServiceshould handle orders, not user authentication. - Open-Closed Principle: Use interfaces and dependency injection in your back-end systems so you can add new data sources, payment gateways, or notification methods without modifying core business logic.

- Dependency Inversion Principle: This is key for microservices. Services should communicate through abstract contracts (like APIs or message queues), not direct implementations.

Using SOLID with Design Patterns (Factory, Strategy, Builder)

SOLID principles and design patterns go hand-in-hand.

- The Strategy Pattern is a perfect example of the Open-Closed Principle.

- The Factory Pattern helps implement the Dependency Inversion Principle by abstracting object creation.

- The Builder Pattern can help manage complex object creation, adhering to the Single Responsibility Principle.

Practical Before-and-After Code Comparisons

The best way to learn is to practice. Take a piece of your existing code that feels complex or brittle. Try to refactor it using one or more SOLID principles. Identify a class with too many responsibilities and break it apart. Find an if/else block that could be replaced with a strategy pattern. The before-and-after difference will often be striking.

What Are the Most Common Mistakes Developers Make With SOLID?

Like any tool, SOLID principles can be misused.

Over-Engineering Code

One of the biggest traps is over-engineering. You don’t need to apply every principle to every piece of code. Applying SOLID “just because” can lead to unnecessary complexity and dozens of tiny classes that make the codebase harder to navigate. Use the principles pragmatically, where they provide clear value.

Misunderstanding Abstraction Layering

Creating abstractions for the sake of abstraction is a common mistake. A good abstraction simplifies and clarifies. A bad abstraction just adds another layer of indirection without any real benefit. Always ask: “Does this abstraction make my system more flexible or easier to understand?”

When Not to Apply SOLID

In the early stages of a project or a prototype, it might be more important to get something working quickly. Applying SOLID principles too rigorously can slow you down. It’s often better to start simple and refactor towards SOLID as the project matures and requirements become clearer. YAGNI (You Ain’t Gonna Need It) is a useful principle to keep in mind.

SOLID vs Other Software Design Principles

SOLID doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s part of a larger ecosystem of software design principles.

SOLID vs GRASP

GRASP (General Responsibility Assignment Software Patterns) is another set of principles for object-oriented design. There is significant overlap. For example, GRASP’s “High Cohesion” is very similar to the Single Responsibility Principle, and “Low Coupling” aligns with the Dependency Inversion Principle. SOLID can be seen as a more specific and actionable subset of GRASP’s ideas.

SOLID vs KISS & DRY

- KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid): This principle reminds us not to overcomplicate things. It serves as a good counterbalance to the potential over-engineering that can come from misapplying SOLID.

- DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself): This principle is about avoiding code duplication. SOLID principles, particularly OCP and DIP, help you achieve DRY by promoting reusable, modular code.

SOLID and Clean Architecture (Uncle Bob)

Clean Architecture, also promoted by Robert C. Martin, is a broader architectural model that organizes a system into concentric circles (Entities, Use Cases, Interface Adapters, Frameworks & Drivers). The SOLID principles are the low-level design guidelines that help you build the components within this architecture correctly. DIP is especially critical for maintaining the dependency rule of Clean Architecture.

Which Programming Languages Are Best for Learning SOLID?

SOLID principles are language-agnostic, but they are most naturally applied in statically-typed, object-oriented languages.

- SOLID in Java / C# and .NET: These languages have strong support for interfaces, abstract classes, and access modifiers, making them ideal environments for learning and applying SOLID.

- SOLID in Python: Python is dynamically typed, but it fully supports classes and inheritance. You can use Abstract Base Classes (

abcmodule) to create explicit interfaces and apply SOLID effectively. - SOLID in PHP or JavaScript: Modern versions of these languages have robust object-oriented features. While their dynamic nature can sometimes obscure design issues, applying SOLID principles is still highly beneficial for building large, maintainable applications.

How SOLID Helps You Build Scalable Cloud and Hosting Applications

The principles of SOLID are not just for local applications; they are essential for building robust, scalable cloud-native systems.

Designing for Multi-tenant Systems

In a multi-tenant architecture, SOLID principles are critical. For example, using DIP and OCP allows you to add tenant-specific customizations or features (like a custom authentication provider) without altering the core application logic.

How SOLID Enhances API Reliability

APIs built with SOLID principles are more reliable and easier to evolve. By using ISP, you can provide different versions or tiers of your API without forcing all clients to adapt to a single, monolithic interface. SRP ensures that each endpoint has a clear, focused purpose, making the API easier to understand and use.

Cleaner Architecture for VPS and Cloud-Hosted Apps

When deploying applications on a VPS or cloud platform, maintainability is key. A clean, SOLID-based architecture makes it easier to manage deployments, scale individual components, and troubleshoot issues. For example, a well-designed application hosted on a platform like Skynethosting.net can be easily containerized and orchestrated, as its components are loosely coupled and independently deployable. This modularity, born from SOLID principles, is a perfect match for modern cloud infrastructure.

Your Path to Cleaner Code

If you’ve made it this far, it’s clear you’re serious about improving your craft as a software developer. So, where do you go from here?

Why SOLID Still Matters Today

In an era of microservices, serverless functions, and complex distributed systems, the principles of good object-oriented design are more relevant than ever. SOLID provides the foundational skills needed to manage complexity at any scale. It’s not a passing fad; it’s a timeless set of guidelines for professional software development.

How to Start Applying SOLID Immediately

- Start Small: Pick one principle, like SRP, and focus on applying it for a week.

- Refactor with Purpose: Find a “code smell” in your current project and see if a SOLID principle can help fix it.

- Discuss in Code Reviews: Bring up SOLID principles during code reviews. It’s a great way to learn together as a team and establish shared standards.

Recommended Tools & Hosting Platforms for Developers

To support your journey, leverage tools that encourage good design. Use IDEs with strong refactoring capabilities, and consider static analysis tools that can spot potential design flaws. And when it’s time to deploy, choose a hosting platform that offers the flexibility and performance needed for modern applications. A reliable VPS or cloud host gives you the control to build and scale your well-architected systems effectively.

The journey to mastering SOLID is ongoing, but every step you take will make you a better, more effective developer.